Beta Readers vs Critique Groups

Both sources can be valuable during your revision process, but you want to consider the contributions and backgrounds of the people involved. Which brings me to the impetus for my post today: I asked too much of my critique group last month.

Critique Groups

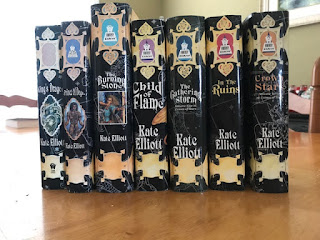

Why? Half of the writers in the group know the story in my upcoming trilogy (releasing in Dec. 2020). They've seen large parts of books one and two. The other half have never seen this work. The Watchers is an epic fantasy trilogy. I'm working on book three and decided to run the opening chapters past the group to see how well it worked. I, also, wanted to know how much they understood, in the case of those who never saw the first two books.

Some members of the group followed my first chapters without a problem, not concerned about the gaps in their memory or knowledge. A few remembered details that surprised me. Others struggled. For the most part, the latter group fell into the ones who never saw the story before; although, I'm glad to say several of them did grasp enough to want to read the first two books.

Our writing group represents all genres. Few of them read or write epic fantasy. At this point in the revision process, I need epic readers with familiarity to the first two books.

Coming into an epic fantasy trilogy on book three can be a bit of a problem. I knew this going in.

(Posts I've written about finding and working with critique groups.)

The Epic

Most epic readers refuse to start in the middle. They find book one and start there. If they do decide to stick with a later book in the series, having not read book one, they expect and accept a certain amount of confusion. They realize the story arc continues throughout the series; you must start at the beginning to grasp the full arc. Some readers even re-read the previous books prior to reading the most recent release. Since epic series can run from three to fifteen books, that's quite a commitment to the story and author.

Let's face it, it's called epic for a reason. Even Merriam Webster struggles to define the term:

As a noun:- a long narrative poem in elevated style recounting the deeds of a legendary or historical hero; the Iliad and the Odyssey are epics

- a work of art (such as a novel or drama) that resembles or suggests an epic

- a series of events or body of legend or tradition thought to form the proper subject of an epic

- of, relating to, or having the characteristics of an epic; an epic poem

- extending beyond the usual or ordinary especially in size or scope

My second grade teacher instructed us not to use the word you're defining within its definition. Websters appears to not know this rule or can't figure out a way around it. Some words, I guess, are harder to define than others. As far as epic fantasy goes, the second adjective definition comes the closest to explaining epic when related to fiction.

The Epic Fantasy

What about the definition of epic fantasy? You'll find a plethora of thoughts and ideas on what it is or isn't. I've provided a few links below where people attempt to explain the genre. While each of these entries have similarities, they don't fully agree on the definition, either.

The genre and its readers know what to expect and love reading the extensive world-building that spans several cultures. They expect a huge cast of characters from those cultures. Someone or something out of the ordinary rocks the world--usually someone seeking to conquer everyone else. There are battles and intrigue. Cultures clash. Characters scatter across the kingdoms creating the need for multiple points of views. The end of book one is not the end of the story. There's a shorter arc that might be fulfilled, but the main story conflict continues in later books.

Epic fantasy readers know these things and expect long books. They joke about the ability to use the books as doorstops. In many cases, the epic story can take many books to complete the overall story arc. (George R. R. Martin anyone?)

Beta Readers

- They comment on the whole story--what works, what's missing, what doesn't work--an invaluable difference from critique groups who see small pieces at a time.

- They invest time into the books and can discuss the full story arc with you when you need to seek someone else's opinion.

- In my case, they continued to encourage me when I started receiving rejections for my work (it's not a matter of if, you will get rejections).

Comments

Finding a good group is key, and I am so happy with ours!

I agree with Alexa. I get a lot of benefit from our critique group, both in their critiques of my pages and in my attempts to critique their pages. I've learned a lot, but mostly I've learned how little I know. When I started, I had no clue readers had expectations for each genre, nor that it's important to meet those expectations. But in order to do that, I have to know what genre I'm writing.

Maybe the problem is that I didn't start out to write any particular genre. There's this story in my head, and I'm trying to get it out. As far as I can tell, it's a mix of several genres. Maybe this is my practice story that no one will ever want to publish because it's such a hodgepodge. I can practice meeting the expectations of all the genres mixed up in it. Ha!

I agree. Our group is amazing, My point is that there’s a time for critique groups and a time for beta readers. I can’t get the feedback I need now because of the extensive world building from the first two books. If this group was fully familiar with the first two books, I’d probably continue to bring it in. Since they’re not, i’m shifting to betas.